Alisha Haridasani Gupta for The New York Times I Photography Erin Schaff/The New York Times

“Black girls deserve to be children.”

— A poem by Azariah Baker, a high school student in Chicago

For the past year and a half, Jamese Logan, a 15-year-old in Lanham, Md., found herself looking after four children. Her aunt died of cancer in May, leaving her children, the youngest just over a year old, in the care of Jamese’s mother.

And when Jamese’s mother goes to work, it has been Jamese’s responsibility to look after her cousins, juggling their needs with her homework and virtual school.

For Yanica Mejias, a 17-year-old in Gaithersburg, Md., these last 12 months have been a huge financial strain. Her parents divorced in November, and Yanica, her mother and her 14-year-old sister moved into the basement of her aunt’s house. Yanica took on extra shifts at a burger restaurant to help keep the family afloat.

“It was kind of like we were starting from zero,” she said.

And Azariah Baker, a 15-year-old in Chicago, has been caring for her 70-year-old grandmother, who had a stroke at the start of 2020, as well as her 2-year-old niece. Her grandmother is the legal guardian for Azariah and her niece but since the stroke, which left her extremely fatigued with blurry vision and headaches, Azariah has done the heavy lifting at home. She would wake up every day at 7 a.m., make them all breakfast, then log on for virtual school at 8 a.m.

When school was out, she’d go to work at a grocery store. Then she’d come back home and cook dinner. She often felt overwhelmed. “I remember one night, I was making dinner and I was having a panic attack. I was crying, I felt like I couldn’t breathe, and my heart was racing,” Azariah said.

“But then my alarm went off for something in the oven,” she said, and she put her own needs aside.

These three stories encapsulate the ways in which the pandemic has affected the lives of young women of color across the United States, even if they weren’t directly touched by the coronavirus. Black and Hispanic youth were more likely to have

lost a parent or a

family member to

Covid-19. They have

fallen further behind in school than their white counterparts, and they had

far higher unemployment rates last year than older adults and young white women, even during the summer, when youth employment typically goes up. Some of those who held on to or found new jobs became crucial breadwinners because their family members were more likely to have been laid off.

Black and Hispanic teenage girls were also more likely than white girls and their male counterparts to

shoulder care responsibilities at home, according to

a report by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. At the same time, they

were leading racial justice demonstrations across the country, most notably last summer, channeling their energy into confronting and changing systemic inequities.

“Black girls were on the front lines of racial justice movements, they were essential workers and they were primary caregivers,” said Scheherazade Tillet, a founder and the executive director of A Long Walk Home, an organization that empowers Black girls in Chicago. “There’s no other group that was all three of those things at once.”

All of this has taken a psychological toll. In June, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported

a sharp spike in emergency room visits after suspected suicide attempts by girls ages 12 to 17 in the first months of 2021 compared with 2019. This is possibly because of “more severe distress among young females than has been identified in previous reports during the pandemic,” the report said, though the study didn’t break down the data by race.

A survey of over 2,000 young people, published in June

by the nonprofit organization America’s Promise Alliance, found that 78 percent of girls ages 13 to 19 reported in the past 30 days at least one sign of decreased mental health, such as feeling distressed or being unable to sleep, compared with 65 percent of boys.

A Long Walk Home found in a survey of about 30 girls that nearly 70 percent reported increased anxiety and an inability to sleep in the last year. Twenty-seven percent reported having suicidal thoughts. Crittenton Services, an organization based in Washington, D.C., and Maryland that supports girls of color, found that out of the nearly 400 girls in its network, 63 percent felt stressed, and half had trouble sleeping, according to an internal survey that was shared with The Times.

“This is the crisis that they have come through,” Ms. Tillet said. “So what systems are in place now to support their emotional and psychological needs?”

Behind the numbers are lives upended, dreams shattered, the burden of suddenly becoming a caregiver or a provider. A Long Walk Home found that many girls in its network felt like they’d lost their childhood, or as Azariah put it: “There was no time to be a child.” And as schools and some workplaces open their doors again, the burdens for these young women are still very present. They may even be greater.

But these are also tales of resilience, of girls who become leaders in their communities and rise to the occasion for their families, with creativity and determination buoying them through crises and chaos.

Jamese Logan

A 15-year-old student at DuVal High School in Maryland who takes care of four children under 10.

“I’m trying to figure out a way to balance it all out,” Jamese said. Photographs by Erin Schaff/The New York Times

Jamese’s aunt learned she had Stage 4 brain cancer in February, and she died in May. Since then, Jamese’s focus has been on taking care of her cousins. Child care for four children was impossible to find and would have been too expensive for Jamese’s mother, anyway.

For months, Jamese spent most of her days with her brother, 14, and cousins at home. The six of them made TikTok videos, played games and danced in the living room. Every now and then, she would treat them to pancakes made with a recipe she learned from her grandmother. She felt responsible for the happiness of everyone else around her.

“I wanted to make sure everybody wasn’t sad or angry,” she said. “I wanted to stay energetic and smiling even though my aunt had just passed.”

At the same time, Jamese found it increasingly difficult to focus on schoolwork, and the spotty Wi-Fi at home didn’t help. Her grades started falling.

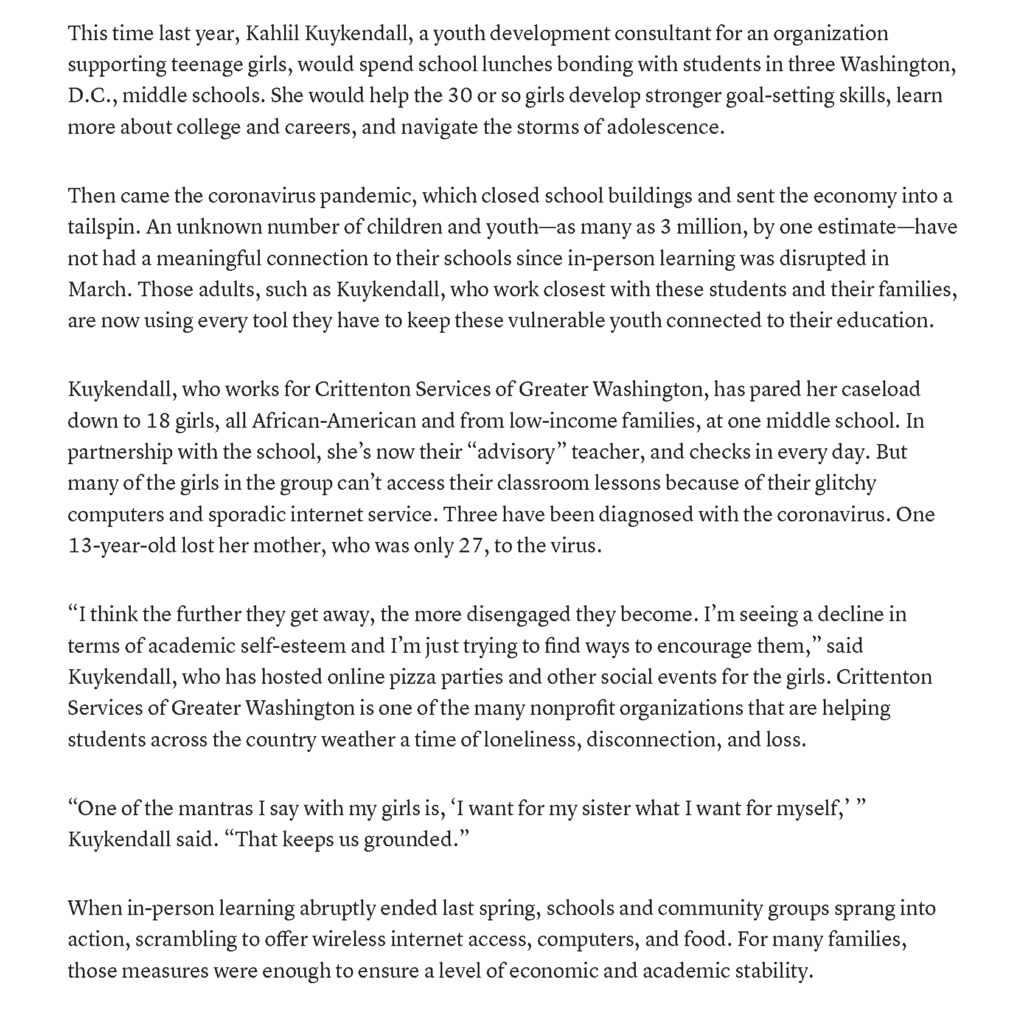

In May, she reached out to Kahlil Kuykendall, a program director at the Crittenton support organization, for emotional help. Ms. Kuykendall, whom some girls call “Mama Kahlil,” made frequent visits to Jamese’s home to check in on her. She also arranged to send Jamese’s family food and money for her aunt’s funeral.

Eventually, with the help of her teachers and Ms. Kuykendall, Jamese’s grades inched back up, and she spent the summer getting her reading score to where it needed to be.

Going back to school in person this month has been “rocky,” she said in a recent phone interview. In the background, her cousins were screaming and crying for lunch. The chicken sandwiches she had made were still cooling in the oven.

Normalcy, Jamese said, would take a little bit of time. “I’m trying to figure out a way to balance it all out,” she added.

Yanica Mejias

A 17-year-old at Gaithersburg High School in Maryland who feels the need to support her family financially.

“Sometimes my sister would ask me if I wanted to go to the pool with her. But usually when she wanted to go, I had to work,” Yanica said. Photographs by Erin Schaff/The New York Times

Yanica used to live in a house where she and her sister had separate rooms. But almost overnight, her parents’ divorce forced Yanica, her mother and her sister all into one room, in the basement of an aunt’s house. Yanica’s job at a local burger drive-through that was once just for “fun” became a lifeline. She now pays her own phone bills and chips in for the car insurance.

The coronavirus pandemic derailed Yanica’s plan to take a course last year to become a certified nursing assistant, so she did it this summer, virtually. Her dream to go to the University of Miami after high school is dependent on how financially stable her family will be at the end of the year — otherwise, Yanica said, she’ll take a two-year course at a community college.

At the burger place, Checkers, Yanica was promoted from cashier to shift manager, taking on more responsibility when the business couldn’t retain workers or lure them back. She made sure that everyone was wearing a uniform and that the store was cleaned. She closed at the end of the day, counting the money and putting it into the system.

Between schoolwork, her job, nurse assistant training and her parents’ divorce, she had less and less time to spend with her friends. When she looked around, they seemed to have had an enjoyable summer break with their families.

“Sometimes my sister would ask me if I wanted to go to the pool with her,” Yanica said. “But usually when she wanted to go, I had to work.”

Yanica recently graduated from her nurse assistant program. She didn’t tell many people in her family because, she said, the ceremony was virtual and it felt underwhelming. “I kind of just kept it to myself,” she said. She didn’t even dress up for the virtual ceremony, or take screenshots of the event.

Other matters demanded her attention the week she graduated: School reopened in person, and her family moved again. She quit her job because of scheduling issues, but now she’s doing a paid internship at a day care.

Azariah Baker

A 15-year-old at George Westinghouse College Preparatory in Chicago who juggles school with caring for her grandmother and toddler niece.

Last summer, Azariah felt compelled to participate in the racial justice movement that was sweeping the country. In an after-school program, she and her friends brainstormed practical solutions to systemic inequality and realized that the recent closure of a local grocery store during the pandemic meant that their neighborhood had limited access to fresh food.

With the help of a nonprofit organization, the 12 high schoolers tore down an abandoned liquor store and

opened a fresh produce market, sourcing fruit, other food and flowers from local suppliers across Chicago. Azariah and the other students work there three times a week.

To balance it all, Azariah multitasked, helping customers one minute, finishing her homework in the corner the next. “I’d have my computer on the counter while I’m setting up a flower station,” she said. Her peers started calling her “Miss President” because of how much she could handle with grace. Azariah was also doing interviews when the story of the new grocery store got picked up by

local and

national press.

But behind the scenes, she was growing worn out, particularly with virtual school and the caregiving — for her grandmother, whom she calls “mom,” and her niece — at home.

“The reality is that a large portion of the time, I’m not OK,” she said. “There’s a part of me that wants to have fun and be a kid and take up space.”

Azariah is now back in school in person. As great as it has been to see friends again, the transition has been stressful. “I live 20 miles from my school,” she said, and the commute means she has to be up by 5 a.m. at the latest. “I am also overwhelmed trying to keep up with schoolwork, go to work after, and I worry about my mom’s physical and mental health.”

In the slivers of time that Azariah had to herself, she wrote a poem:

I would like to write a poem to honor my girl/friends

to the ones who pushed pins into their skin

and the ones who were forced under someone else’s

to the ones who smile in the midst of a battle zone

and to those who carry the battle zones in their hearts

to the ones that always look for something to smile about

with their broken eyes and

eyes that don’t grow weary and

eyes afraid to close

This is a poem to the black girls who have cried about being a black girl

Who filled their bodies with hate and envy and disgust

Hate, and envy, and disgust

Hate, and envy, and disgust

Breathe.

Black girls deserve to be children.

See original article

Alisha Haridasani Gupta is a gender reporter covering politics, business, technology, health and culture through the gender lens. She writes the In Her Words newsletter. @alisha__g